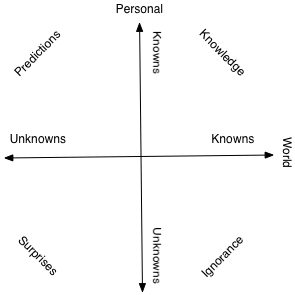

Reports that say that something hasn’t happened are always interesting to me, because as we know, there are “known knowns”; there are things we know we know. We also know there are “known unknowns”; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also “unknown unknowns” — the ones we don’t know we don’t know.

— Donald Rumsfeld, U.S. Secretary of Defense,

Defense Department Briefing on February 12, 2002

I have drawn a diagram of this constellation below. I like drawing diagrams because they often point out things we miss. Things we miss can cause all sorts of trouble. In this case what was missing from Rumsfeld’s statement (and thinking?) were “unknown knowns”. These are that which we don’t know but which we could know, because other people know them. “Unknown knowns” are also called ignorance and are often a consequence of certitude or faith.

The entire quad looks like this

One particularly profound source of personal ignorance and surprises is specialization. Specialization drives a person into the upper right corner where he knows everything there is to know about nothing. People may be surprised to learn this but despite often being asked their opinion on current events actors generally don’t know much about politics whereasthey do know a lot about acting 😛 . The same goes for other vocations. A more serious example might be that of the scholar. Scholars or researchers are vocationally rewarded for their productivity as measured by the number of publications in prestigious journals. While there is lots of focus on work-life balance and entertaining alternative hobbies, those who focus 100% of their energy on their specialization eventually gets the promotion. This has lead to a lot of ultra-focused intellectuals each driving a specialized understanding of a narrow fraction of the world but few tying it all together.The result is specialists that have a hard time communicating to the broader public and even to each other. There are no singly organizing humans that are capable of learning everything there is to know anymore. For instance, there used to be philosophers. Philosophers would think about the world. Philosophers then split into natural philosophers and “other”. The natural philosophers later became mathematicians, physicists, chemists, astronomers, geologists, biologists, … and not so long after that these split up as well. Thus today it is very hard to place knowledge into context.

Therefore putting things in context is not done by individuals. Rather it is done by procedures or delegation by a system. Now the problem is that specialization has caused an attitude where it is implicitly assumed that there is always a “they” that can solve any problem. Global warming? “They” will think of something! Flu epidemics? “They” will think of something! Running out of oil? “They” will think of something!

The problem is that there is no “they” in charge of the world. “They” may be able to fix isolated problems like a gas chromatographic analysis of ear wax, but “they” are not able to fix systemic problem. Systems have inertia. Lots of inertia. Did you ever wonder why English as taught in schools focuses the analyses of texts often perpetrated by crazy people, you know, writers, rather grammar or writing copy or journalistic articles or simply letters? Students are essentially imitating English professors, who are imitating medieval monasteries, who are imitating ancient Greek philosophers (read more here). Architecture is another example. Why do big institutions have Doric columns imitating stone facades of Greek temples which again imitate wood pillars of simpler huts? Why do universities still have seminars dating from a time when communication was so slow and expensive that students could not afford their own textbooks? It’s systemic inertia and the reason for the systemic inertia is that there is no “they” in charge of operations.

This becomes a big problem when it comes to future planning. For instance, financial planning is mostly based on historic returns even though everyone warns us that past results are no guarantee of future returns. The question we must ask ourself is not what the known unknowns are e.g. whether future returns of the stock market indices are 4%, 8% or 12%, but rather what are the unknown unknowns? Will democracy still exist in 30 years? Will the dollar be worth anything? Will barter rather than monetary exchange be the focus? Will everybody be entrepreneurs rather than employees? Will world war III occur? Will people be expected to grow their own food or will food be provided in the form of soylent green by pipeline? Few retirement plans in the form of 401(k)s, IRAs, SEPs, etc. make provisions for this, because financial planners are, sadly, experts in financial planning.

There are two strategies to pursue here. The comfortable one is to follow the crowd and do what everybody else does. This is safe in the psychic sense. Note for instance, that since very many people were stupid and speculated in eternal growth of real estate prices they did get a bailout. Individuals do not fare this well because democracy cares less about individuals. However, individuals are nimbler and more agile than crowds, so this makes for an alternative strategy which is the one I prefer. But this strategy is not all about accumulating a million dollars. It is also about the situation where money doesn’t buy you anything.

Originally posted 2008-03-17 07:12:24.